The canyon country of western Colorado is greatly underappreciated as a backcountry destination. It has basically the same geology and topography as the red rock country of Utah, but without the Moab-centered crowds of hikers, campers and off-roaders. It’s also a good deal closer to Boulder.

I’ve long had Rattlesnake Canyon on my radar. It has more arches than any place outside of Arches National Park. It’s likely you’ve never heard of it, and almost certainly you haven’t gone there. The reasons why should become apparent as you read on.

Arches NP has become a zoo, where reservations are required not only for camping, but just for entry. It’s another node in the Moab industrial tourist complex.

Entrance to Rattlesnake Canyon is not free. However, the price of admission is not in dollars or the time spent online reserving a spot, but rather an 8-mile hike (one-way) on a primitive trail with some 3000 feet of elevation gain as you climb (sometimes literally) in and out of intervening canyons.

There is an alternate route that is just a couple of miles, but the trailhead can be reached only by a very bad jeep road. My cousin Mary Kay who lives in Grand Junction reports that she gave up after a couple of hours of crawling up the road, rode her MTB the rest of the way, and still had to turn around at the first arch as it was getting near nightfall.

So that’s why these arches are unknown and why I don’t mind giving away their location.

Besides getting out on a fall trip I had an additional motivation. I lead trips for the Sierra Club’s ICO program, which takes low-income kids on wilderness trips. We have a gear depot at a local middle school that stocks everything needed — tents, backpacks, sleeping bags etc.

For many years we’ve done a spring 4-day trip to Canyonlands NP. But since the pandemic, the demand for backcountry permits has gotten crazy. We were not prepared for this last year and got shut out of our preferred dates and destinations. I planned to scout Rattlesnake to see if it might be a reasonable alternate canyon country trip without the permit hassles.

I got to the Pollock Bench trailhead around 2 pm, saddled up and began the climb up the first high bench. The well-signed trail wound around the bench top for a while, then plunged down a canyon wall, a few spots requiring hand holds and butt scooches to navigate. At least for me — my balance is deteriorating with age and I move slowly and cautiously these days when traversing steep exposed terrain. The climb out was steep but required no scrambling.

The trail meandered across a pinyon-juniper grassland through Kayenta Sandstone buttes, then dropped down again, this time into Pollock Canyon. I missed the easiest drop down point into the canyon and walked about a half mile further along the ledge until it became clear that there was no way down in that direction. I backtracked, found the right gully, and made the canyon bottom with only a few scrambles.

One of my goals in scouting the area was to look for water. Although I was carrying 8L of water (well, 6L plus two Coors tallboys), there is no way that middle-school kids could carry that much on an ICO outing. An on-trail water source is a must for taking kids here. It’s been a dry fall in Colorado, so any water I found now would certainly be present in the spring.

A cluster of cottonwoods along the canyon bottom suggested water, and I did find a seep under a rock slab not far downstream from them. There was a bit of salt encrusted on the banks, suggesting it might not be the best water source. But it would be better quality in the spring.

I didn’t want to camp in the canyon (canyons are cold and sunless this time of year) and climbed on out. It was steep, mostly easy, but there was one exposed rock face traverse that would not be suitable for inexperienced hikers.

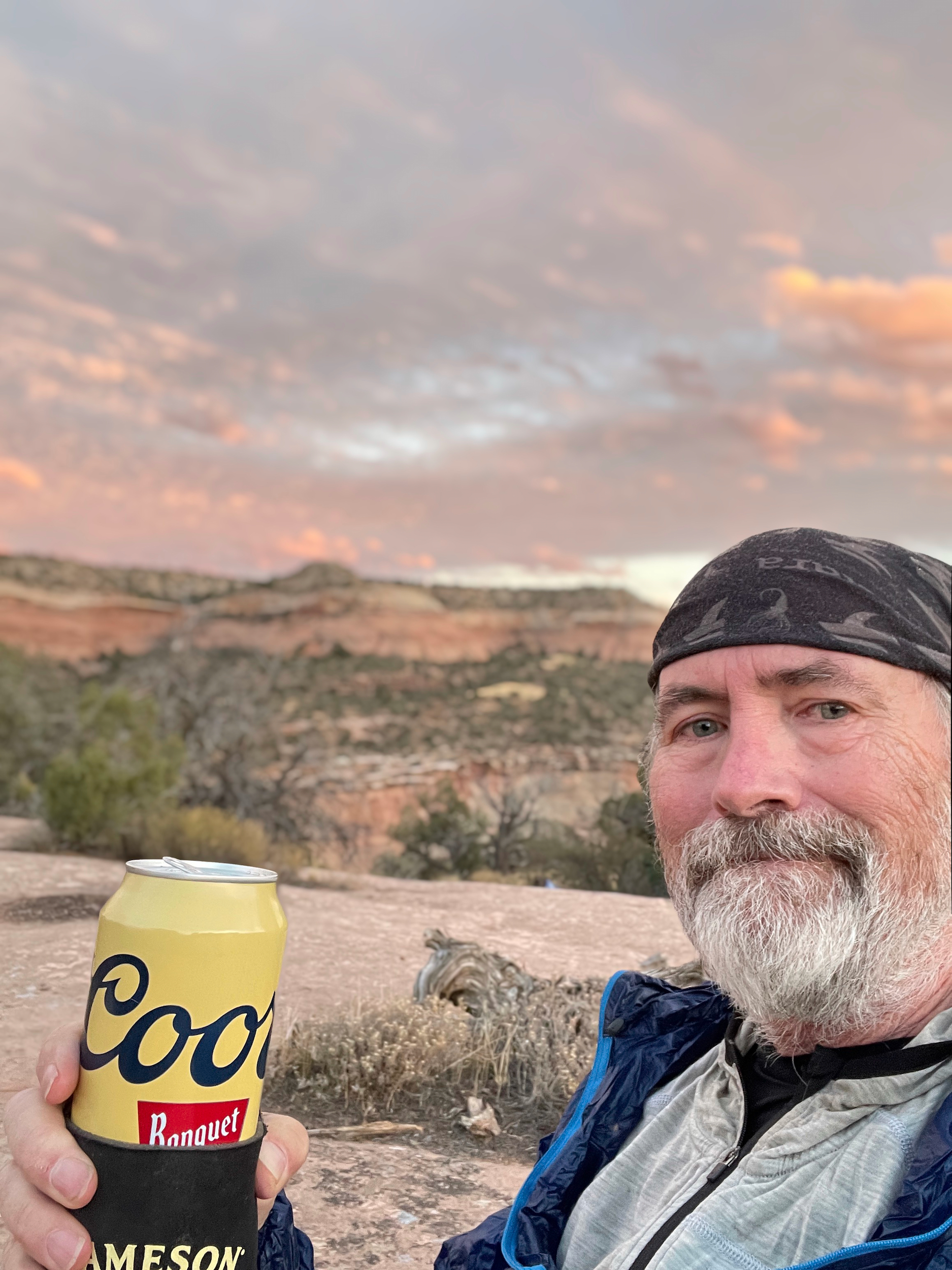

The sun was getting low, so I scouted out a benchtop campsite and settled in to enjoy the sunset on this warm fall day.

I woke to clouds and a light drizzle. The drizzle soon passed and the skies slowly cleared as I made my way up the steep trail to the butte that defines the south wall of Rattlesnake Canyon.

There is a low trail that wraps around the butte and is twice as long as the high trail atop the butte. I took the low trail, reasoning that it would provide better views of the arches.

I was not disappointed.

I found 8 arches in all. They looked very handsome.

In the way back I took the side trail that connects with the upper trail on top of the butte and followed it to a couple of arch overlooks.

The views from above were pleasing but not nearly as dramatic and well formed as from below. The second arch was not even visible from above.

I took numerous detours on the way back, scouting potential campsites and water for an ICO trip. There were some potholes in a side canyon bottom, a water source that is clearly depended upon by desert bighorns. I wouldn’t use this water in the summer or fall, but there should be plenty of water to go around in spring.

There are not many good sites that are away from the trail. Most of the flat spots are cryptogamic soil and are thus inappropriate for camping. But I did find a couple of gravelly sites.

There was little light left by the time I returned to camp, just enough to drink a Coors in the last rays before sundown.

It chilled off quickly then and I used my Caldera Cone to build a fire. It kept me outside for an hour longer than otherwise, so that worked out well.

The morning was clear and sunny. I enjoyed a leisurely breakfast, packed up, and returned to the trailhead, again scouting out campsites and alternate routes.

I stopped in at my cousin’s for a sandwich and a beer, then headed back to Boulder feeling well-satisfied with this trip.