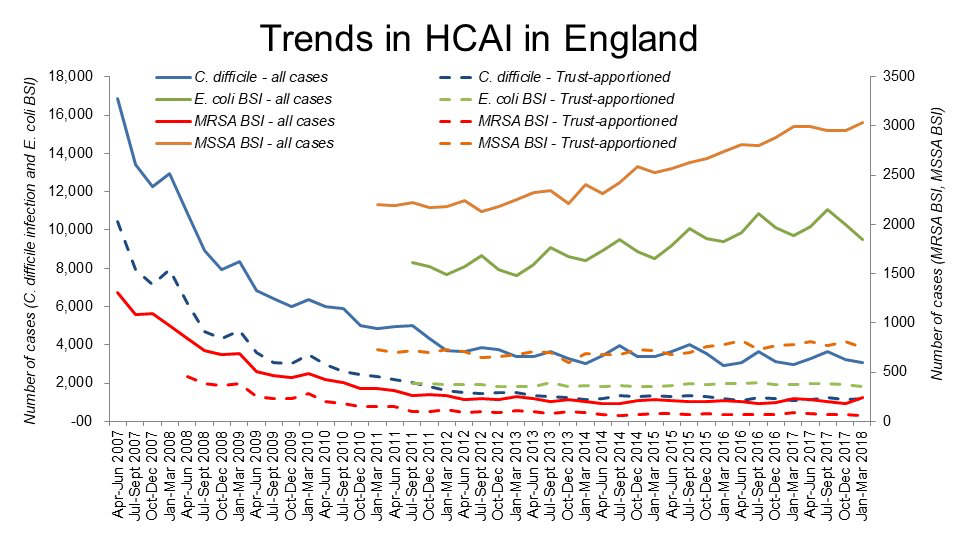

Jon Otter tweeted out this graph today, and it just blows me away:

“Trust apportioned” is apparently the term in UK English for what we in the US call hospitals. So the dotted lines are hospitals and the solid lines include community cases. Huge drops in C diff diarrhea and MRSA BSIs. This is the English MRSA Miracle, expanding out into other hospital-acquired infections.

This is important – thousands of lives are being saved. Yet because it is the result of many small interventions rather than one big breakthrough, you probably won’t read about it in the popular health press. That’s a shame.

In fact, it is downright dumb. Infection control has long been the red-headed stepchild of medicine: usually ignored, except at budget time when it is likely to take a beating. Yet it has the potential to save many more lives than other interventions that hog all the glory (and funding).

Let’s take a look at infection control versus my personal favorite for an overhyped intervention, personalized cancer medicine.

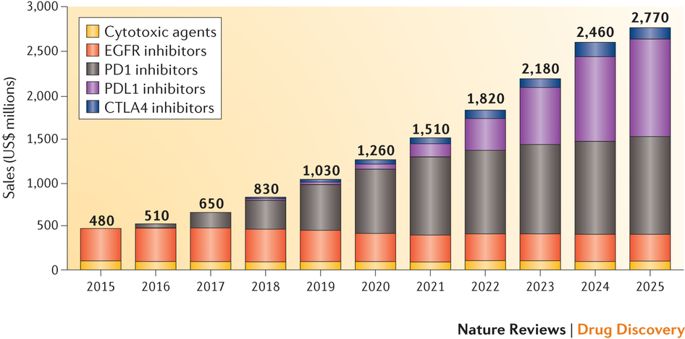

Personalized medicine is a gargantuan business. Sales for PM in just one category – head and neck cancers – already dwarf those of standard cytotoxic therapies, and the gap will only widen. The same story is playing out for nearly all major cancers.

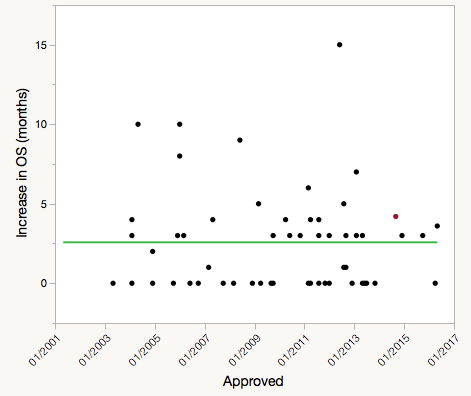

But cost is not the same thing as value. These new medicines have therapeutic value to be sure, but not nearly as much as you might think. Post-marketing studies show that the typical gains in survival are just a few months as compared to cytotoxic agents:

Data mostly from Assessment of Overall Survival, Quality of Life, and Safety Benefits Associated With New Cancer Medicines. Red dot is Keytruda, the best-selling PD1 inhibitor.

The upside for PM is limited. Vinay Prasad estimates that PM treatments cover maybe 8% of all cancer patients now, and could conceivably expand to cover 15%.

There are about 600K deaths per year in the US from cancer. Per the graph above, the new personalized medicines add about 2.7 months of survival over standard therapies. 600,000 deaths x 0.15 PM treatments x 2.7 months of life saved per treatment = 20,000 life-years saved per year by PM. This is perhaps a too-simple way to do this calculation, but it’s good enough for an estimate.

What’s the potential for infection control? The incidence of HAIs is estimated at 1.7M and deaths at 100K in the US in 2002. That’s out of date, but I can’t find a good more-recent estimate, and the CDC is still using it, so I will too. This paper estimates an incidence of 512 HAIs per 100K and 380 years of life lost from HAIs per 100K in the EU. That is probably similar to the US. Dividing 380 years of life lost per 100K by 512 HAIs per 100K gives us 0.74 years of life lost per HAI. So each HAI prevented saves about 9 months of life. That’s more than three times as much life as is saved by a PM cancer treatment.

Multiply that 9 months per HAI x 1.7M HAIs, and you get 1.3 million life-years saved if you could eliminate all HAIs, versus 20 thousand life-years saved by personalized cancer medicine, if it indeed is extended to 15% of all cancer cases.

Of course, eliminating HAIs completely is just not possible. But we can do far better than the status quo. This paper estimates that over 50% of HAIs are “reasonably preventable”. That would yield 600K life-years saved vs 20K for cancer PM. Jon Otter’s results show that this number is not a fantasy. Even if we reduced HAIs by only a small fraction, let’s say 10%, the number of life-years saved would dwarf that of what’s achievable with personalized medicine. And I doubt the cost of preventing an HAI is anywhere near $100K+ spent for a course of PM therapy.

The NIH spends about $5B/year on cancer research. That’s too little, in my opinion. But the CDC’s funding for HAI research? A miserly $12M. That’s $8,000 of research funding per cancer death, and $120 per HAI death.

This is really not OK.

2 thoughts on “Infection control saves more lives than personalized medicine ever will”