Our healthcare system is oriented toward cures, not prevention. Outlays for public health measures have never been more than 2-3% of total healthcare spending, and this small amount is falling – even though we know that every dollar spent returns several dollars in benefits.

We could blame greedy doctors or pharmas or hospitals, or more abstractly, the fee-for-service system in the US for this state of affairs, but that would be pointless. It’s human nature to avoid spending money on distant and low-probability risks. It is equally in our nature to spend lavishly once we lose our bets and join the ranks of the afflicted.

One’s risk of getting a hospital-acquired infection in the US is not very high – about 0.5% in any given year. The risk of dying from an HAI is even lower (0.03% per year).

And these numbers have always been shaky and subject to dispute – nearly everyone who gets or dies from an HAI has some other contributing factor – cancer, diabetes, kidney failure or just plain old age.

Thus it was relatively easy for healthcare practitioners and administrators to rationalize away the fact that people under their care were acquiring new illnesses. Especially when cheap and effective treatments – that is, antibiotics – were available. Antibiotics covered up a multitude of sins – poor hygiene or surgical technique, excessive or poorly prepped catheters, inadequate patient monitoring, etc. They made life a lot easier and more comfortable for healthcare providers, especially the mediocre ones (who by definition are the majority).

Until, of course, our old antibiotics stopped working so well, and the pipeline of new replacements dried up. This meant that a system that was comfortable and working well (for healthcare providers anyway) was no longer acceptable. Numerous stories and books about superbugs and impending apocalypses simply had to be responded to, at least when it became clear that waiting for the next broad-spectrum antibiotic was no longer an option.

And also when it became clear that Medicare was no longer going to foot the bill.

What Winston Churchill said (maybe) of America – that it can be counted on to do the right thing after all other possibilities have been exhausted – is also true of hospitals. Once it was no longer possible to control HAIs with antibiotics (or to get paid for inflicting infections), they began reducing them.

I’ve referred before to the English MRSA Miracle, in which MRSA bloodstream infections were reduced by 90%. But the English are not unique. Our own VA, which might be the closest American analogue to Britain’s NHS, reported last year that it reduced MRSA infections 80-90% over an 8-year period:

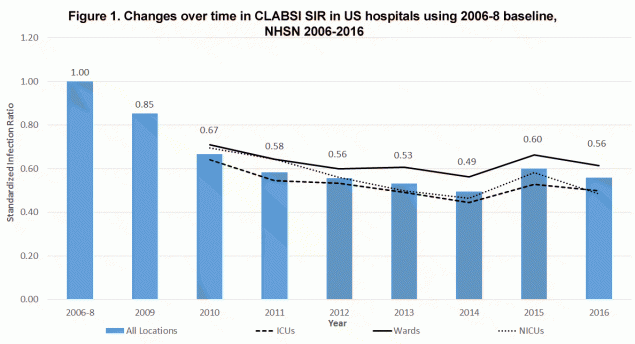

The VA is also not unique, nor is the trend confined to MRSA. Here’s the drop for all Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections in all US hospitals:

From Data Summary of HAIs in the US: Assessing Progress 2006-2016

Other causes show similar improvements.

Let’s agree that it is far better to not get an infection than it is to get one and be cured by antibiotics. HAI rates were flat or increasing before MRSA rates took off in the late 90s and when Gram-negative resistances (ESBLs and CREs) started making those bugs much less treatable. Antibiotics were (and are) wonder drugs, but they were also a crutch that enabled bad medicine.

To their credit, hospitals are now engaged in the hard work of doing their business without leaning so heavily on that crutch. They are making fewer people sick than ever before.

And for that, I contend, we can thank the emergence of antibiotic resistance.

1 thought on “Is antibiotic resistance improving healthcare?”