Doctors are taught that it is important to finish out a course of antibiotics, and they dutifully relay this information to their patients. But the determination of therapy duration is usually based on almost no evidence at all. This is especially true for our understanding of the risk of the development of resistance, which is rarely a measured outcome in the clinical testing of antibiotics. As one review of the subject puts it “Therapy duration is one of the major understudied areas of infectious diseases therapeutics.”[1] . The truth is that in almost no cases do we have a firm evidentiary basis for optimizing therapy duration of antibiotics.

How can this be so? How can something that every conscientious practitioner of medicine “knows” be based on no evidence? There are several drivers responsible for these gaps in our knowledge:

- Antibiotics are too effective. The gold standard in clinical trial design is the placebo-controlled randomized trial. But soon after antibiotics were introduced, it became obvious that withholding antibiotic treatment from a control group was unethical, as it exposed them to a high risk of disease and death. Few placebo-controlled trials of antibiotics have been performed since 1950. Instead, a new antibiotic agent is compared to an existing one, and if it appears no worse than the existing agent, it is deemed “non-inferior” and is approved on that basis.

- Antibiotics are too safe. Most antibiotics, particularly the ß-lactams like penicillin and cephalexin, are very well tolerated. Adverse events are rare, and are fairly minor – diarrhea and allergies are the principal side effects. Thus there is little incentive to minimize either the dose or the duration of antibiotic treatment, and few trials are designed to do so.

- Suppressing resistance is not a priority. The typical end-points for trials of antibiotics are patient cure/improvement and microbiological eradication. Monitoring the fraction of resistant bacteria in an infection during or after a course of treatment is rarely done.

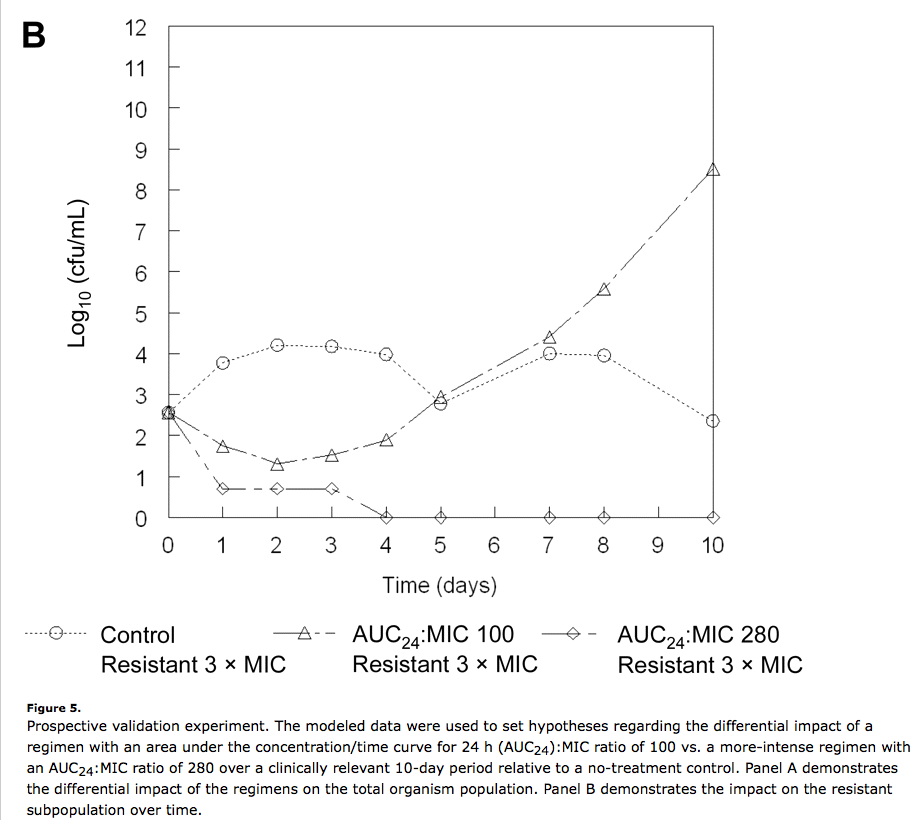

- The development of resistance is usually quantal, not incremental. The “finish your course” treatment paradigm is based an implicit assumption: that resistance develops in a series of steps that cumulatively ramp up resistance levels from zero to weakly to moderately to fully resistant. This certainly happens in the lab, but it is not the dominant mode of resistance acquisition in the clinic. Instead, there is a tiny fraction – maybe one in a million or less – of fully resistant bacteria already present in the infection. The continued use of antibiotics gives this subpopulation the advantage that they need in order to outcompete the susceptible population:

Recognizing that overlong courses of antibiotics are likely to promote the development of resistance, some doctors are working to develop algorithms that reduce antibiotic exposure. Jean Chastre’s group in Paris has shown that procalcitonin levels can be used to discontinue antibiotic therapy in pneumonia patients without impacting patient outcomes[2] . Others have shown that short-course therapy is just as effective as standard courses for intra-abdominal infections[3] and Strep throat[4] .

Antibiotics should always be taken as prescribed. Although we rarely know that a given treatment duration is optimal, we do at least have some evidence that it is safe and effective. Some evidence is always better than none. As the drawbacks to antibiotic use become more evident – increased risk of resistance, obesity, diabetes, and inflammatory diseases – there is more interest in limiting antibiotic exposure in clinical practice. We can expect to see more studies which indicate that less is often more in antibiotic use.

Featured on Huff Post

Footnotes

[1] Suppression of Emergence of Resistance in Pathogenic Bacteria: Keeping Our Powder Dry, Part 1

[2] Procalcitonin to guide antibiotic therapy in the ICU.

[3] Patients with Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infection Presenting with Sepsis Do Not Require Longer Duration of Antimicrobial Therapy.

[4] Short-term late-generation antibiotics versus longer term penicillin for acute streptococcal pharyngitis in children.