High contagion in a world of low trust

Coronavirus morphology. From the Centers for Disease Control, public domain.

The death of Dr. Li Wenliang was not just a human tragedy. The man was a genuine hero, a doctor felled by a disease contracted from a patient. The practice of medicine can be overly transactional, more focused on the acquisition of wealth than the relief of suffering. But it can also be a truly noble profession. The example of Dr. Li, and that of other care providers who risked and lost their lives, reminds us of this truth.

Scan of graphite on paper sketch of Li Wenliang. Done on lightbox over enlarged and desaturated photograph from here: https://kknews.cc/society/naonj53.html. By Mvolz / CC0

Just as Dr. Li was a hero, so the Chinese authorities were villians. Their actions were monstrous. These authorities (you can read their admonition here) muzzled Dr. Li, preventing him and other Wuhan medical personnel from raising any alarm, or even discussing the possible emergence of a new virus.

Suppression of speech in the name of social order is an everyday occurrence in China. But mindless repression usually doesn’t lead so directly to an international health disaster.

It’s easy to connect the dots here: early warning of a new disease is suppressed > disease is not stopped when most controllable > disease spreads widely and rapidly > thousands die.

And it’s also easy to imagine a virtuous alternative scenario. The warnings of Dr. Li and others are taken seriously > prompt and effective control measures are implemented > the lives of thousands are spared.

Success is not an option

Unfortunately this alternative scenario is a fantasy. Not just in China, with its authoritarian priority on social control. If anything, Western countries are worse.

To see why, let’s examine the counterfactual scenario. Here is how it would play out:

●A new respiratory virus arises and begins killing people. But it is not obvious that it is a new virus. It is impossible, without expensive testing, to distinguish viral pneumonias from one another. Since this is a new disease, there are no tests for it anyway. The possibility of a new virus emerges by process of elimination, after a number of patients test negative for all known viruses.

●The new virus is isolated and its genome is sequenced. But the value of genome data is limited. It can’t tell us much about how virulent or how contagious a virus will be. That information can only be obtained by observation. Accurate observation requires time and numbers. In other words, the probability of an epidemic is very uncertain in its early stages.

●Despite the inherent uncertainty, expert infectious disease specialists decide to raise the alarm. They go to the civil authorities and express their worries. The authorities listen, are appropriately concerned, and ask what measures should be taken (this is the counterfactual part, what everyone agrees should have happened).

●The scientists respond: track the contacts of every victim; place these contacts under surveillance; go door-to-door to identify possible victims and place them under quarantine; close the schools; ban public gatherings; issue travel alerts and screen travelers at airports, train stations and major highways, or close them down altogether*.

●The authorities respond: “Are you fucking crazy?”

No, the docs are not crazy. They are giving well-considered advice that best reduces the potential for infectious disease catastrophe.

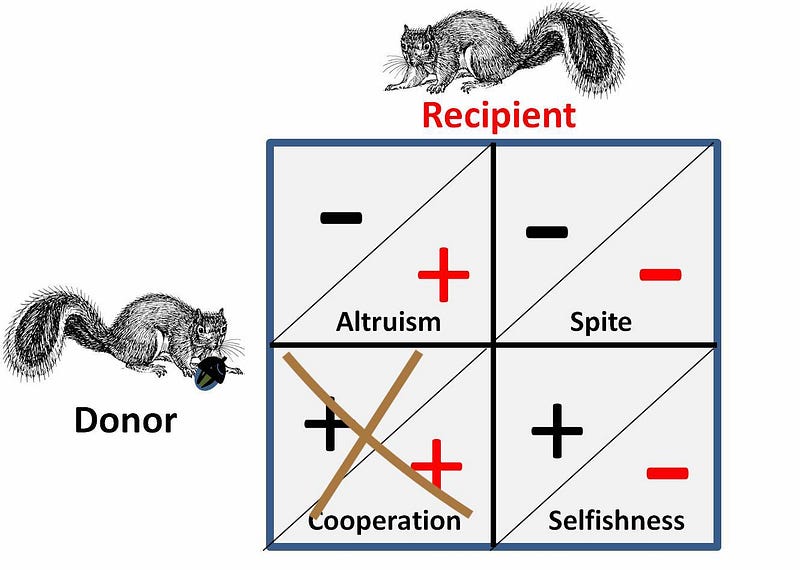

Game theory gone bad. My alteration of a diagram by Pearson Scott Foresman / Public domain

And the authorities are not monsters or idiots. They have been put in an impossible position, and they know it. Gaming it out, there are four possible scenarios. Each of them, at an early stage of uncertain and conflicting information, is equally likely:

- Deadly virus, no lockdown — This is the Wuhan scenario, where the authorities do too little too late and a deadly virus escapes. Thousands die and the economy is severely disrupted. The authorities are blamed and punished.

- Weak virus, full lockdown — Another nightmare. The lives of millions are disrupted by a false alarm. Economic losses are in the billions. Lives are lost — not to the virus, but in the resulting disruption. The authorities are blamed and punished.

- Deadly virus, full lockdown — The epidemic is contained and thousands of lives are saved. Success! But these lives are saved only in theory. Nothing actually happened. Justifications based on complex epidemiological models are dismissed as self-serving hot air. In contrast, the disruptions caused by the lockdown were very real and very serious. The authorities did exactly the right thing—and are blamed and punished.

- Weak virus, no lockdown — The only possible win for the authorities. No action is taken, but there are few deaths and no disruption. The authorities (if noticed at all) are praised for their common sense and good judgement.

Cassandra’s accurate prophecy of the fate of Troy (left) and her reward (right). kladcat / CC BY

The tragic nature of public health

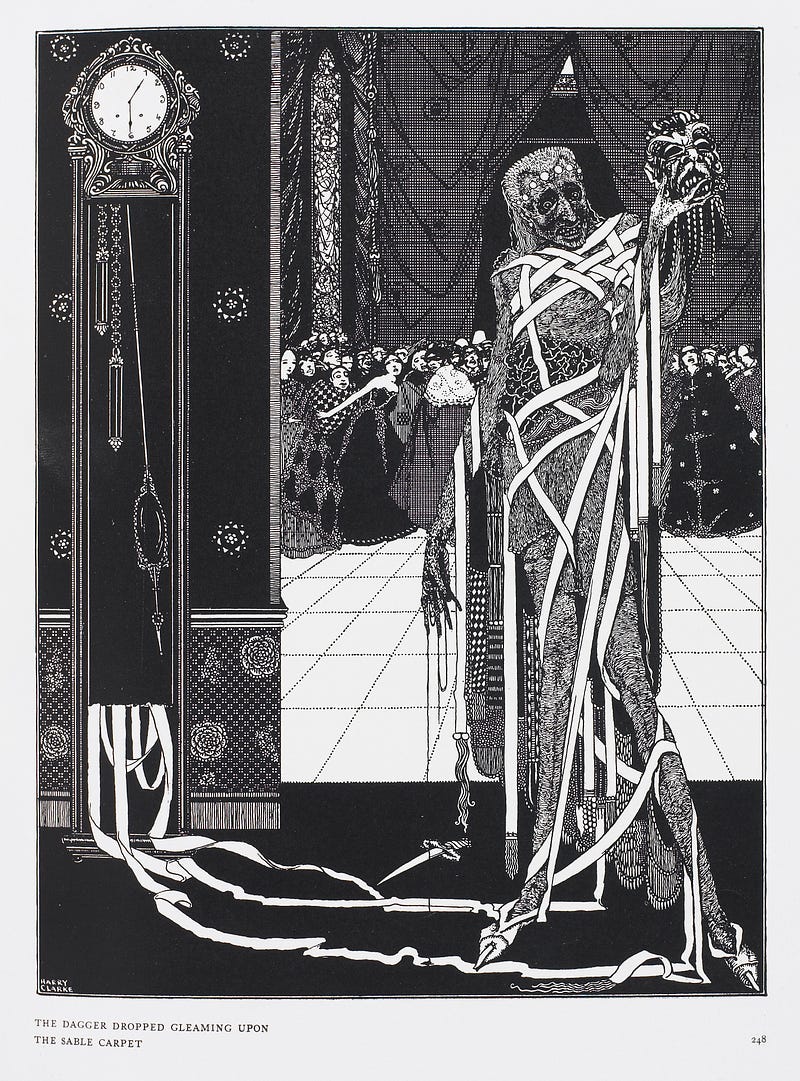

The essence of tragedy is doom. No matter what choices the actors make — good or bad, wise or foolish — they are powerless to affect their own fate. That fate is usually evil.

It is just so with any successful public health effort. The costs are always real and immediate and easily comprehended. The benefits consist solely of things that did not happen. You get no credit for that.

The only environment in which the authorities are credited for things that do not happen is one in which those things happen frequently.

That was the world of the 19th and early 20th centuries, in which infections caused more than 2/3rds of all deaths, and most parents lost a child to disease. Deaths from infectious disease were an everyday experience. Any reduction in those deaths — from vaccines, public hygeine, quarantines — was immediately noticed and credited.

The success of these measures made them ignorable. Infectious disease now kills few, mostly the old and infirm. We fear cancer, not smallpox or polio. We no more notice the benefit of public health than a fish notices the benefit of water. Without the power of fear, public health has no power at all.

This will happen again

The authorities in Wuhan behaved very badly. They did wrong, and thousands will die. But would we do better? Have we done better?

We would not instigate a formal humiliation like the one inflicted on Li Wenliang. We instead inflict the informal humiliation of disbelieving our own Cassandras. Or, if we listen to their advice, we blame them for the costs incurred and withhold credit for lives saved. Public health continues to be underfunded, its practitioners the lowest-paid of any medical speciality.

Public health can only function in a high-trust environment. Its costs are immediate and real. Its benefits are delayed and intangible, expressed in esoteric statistics of deaths avoided. That is insufficient to overcome our current distrust of scientific elites, our glee in mocking scientific expertise as junk science. Populism is having its party, but doesn’t know who is on the guest list.

*This is pretty much what the Wuhan authorities have done, albeit belatedly.