I’ve ragged on various phage groups for what I perceive as their shortcomings in moving phage therapy from proof of principle to an actual product that can be used to treat patients reliably.

There are plenty of anecdotal reports and case studies of patients helped by PT, and I’m sure that many of them are true. After all, the principle is sound.

But principles and products are two very different creatures. Growing enough phage to do experiments in the lab is easy – that’s why phage were so popular as a model system, particularly among physicists like Max Delbruck and Francis Crick who were not particularly adept laboratorians.

Making phage into a product that is exactly what you think it is, and will behave as expected every time, especially in the hands of other folks (doctors and nurses) who know nothing about phage and are not particularly interested in learning – that’s another story.

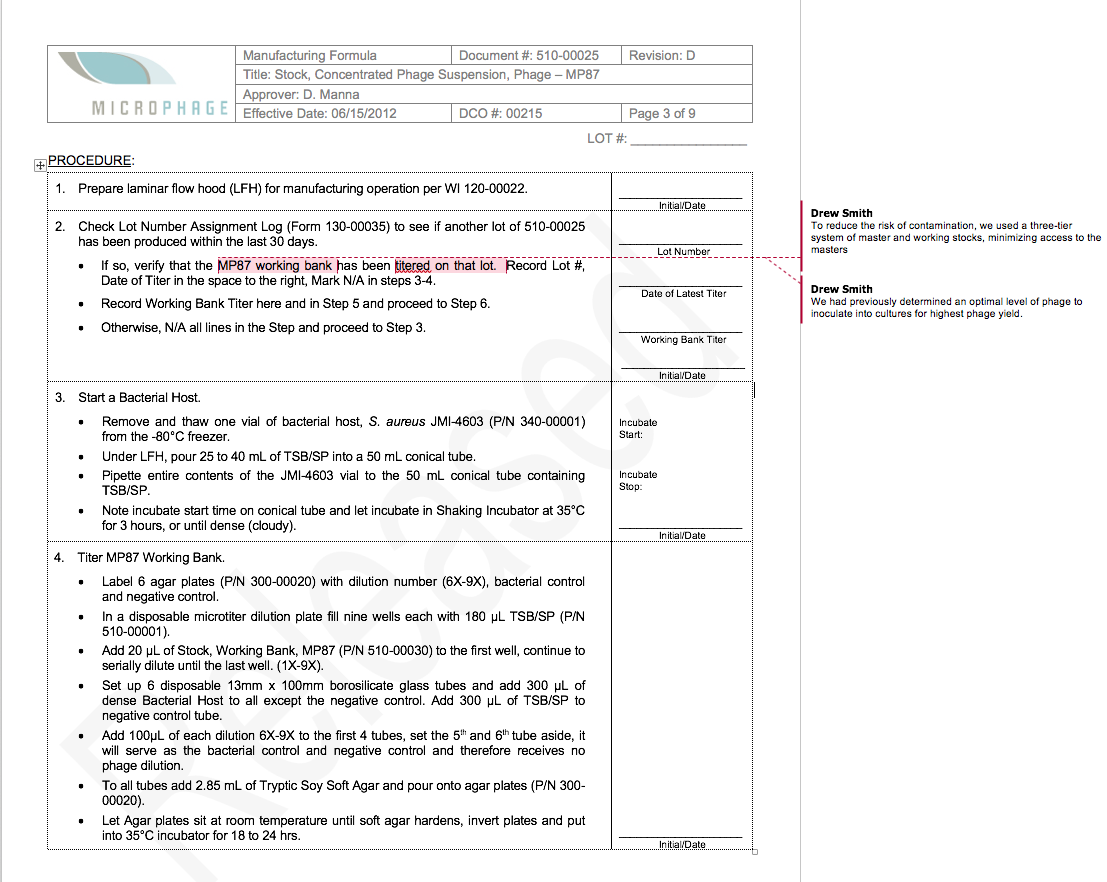

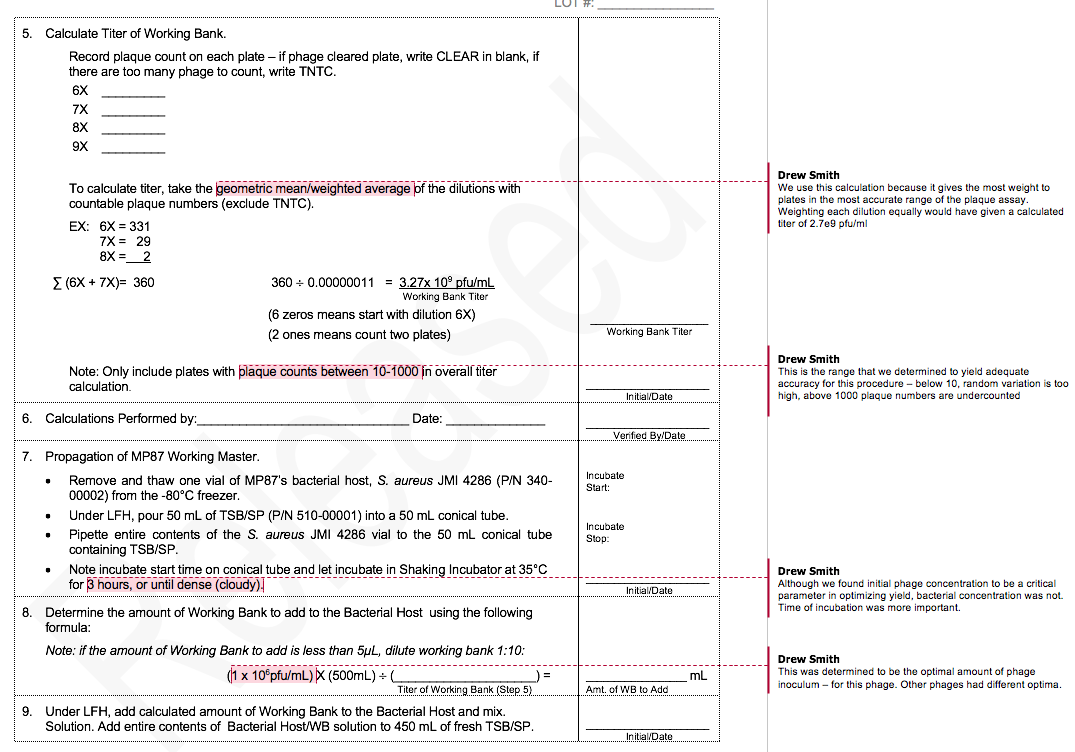

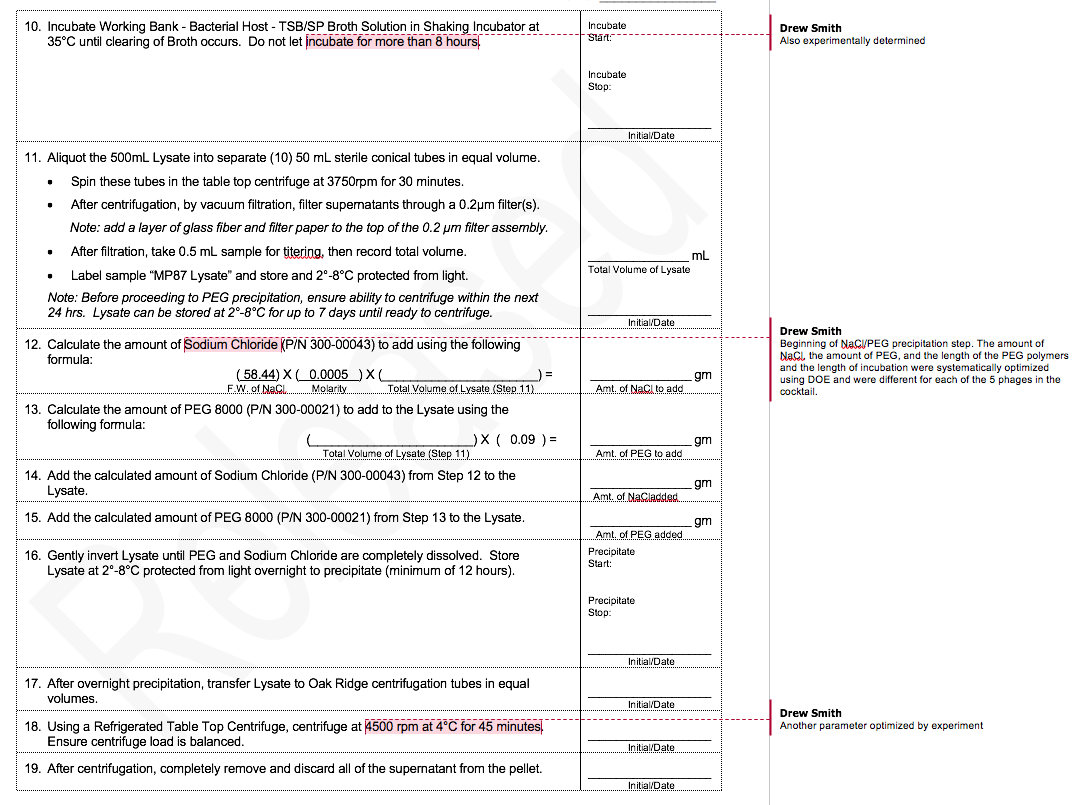

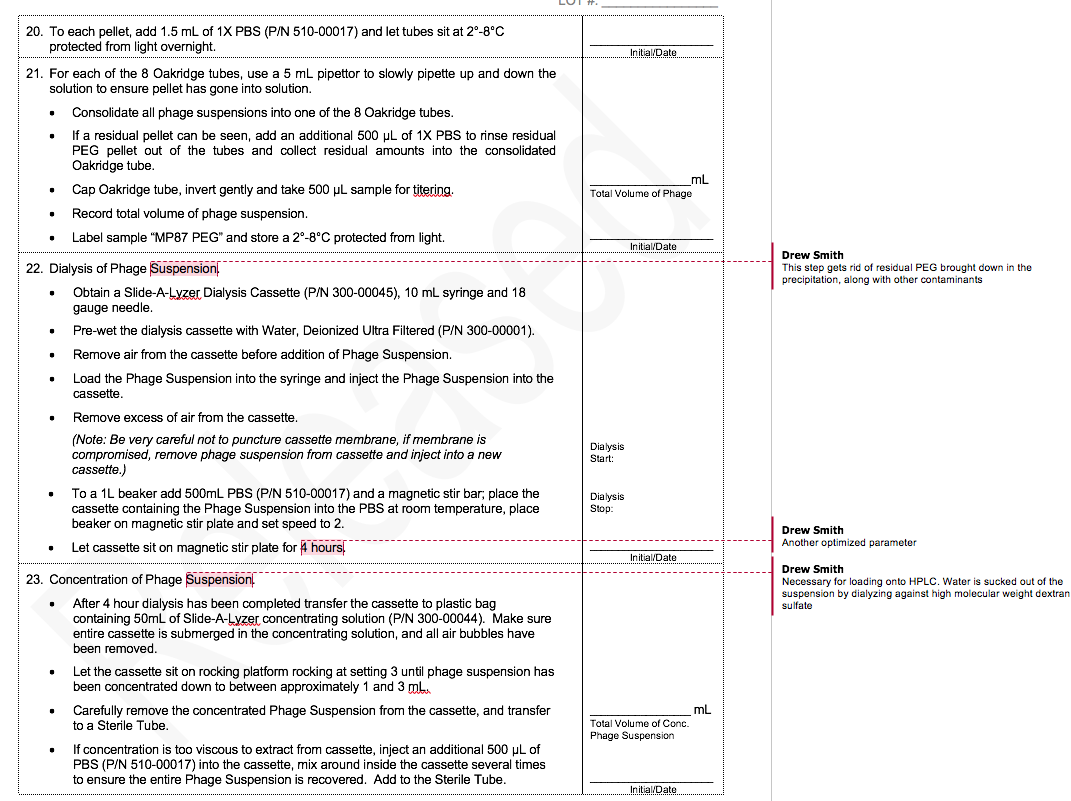

Modern medicine demands that formulations and devices be produced under quality control systems that assure end users of reliable performance. A key component in quality assurance is what’s known as Good Manufacturing Practices. One aspect of GMP manufacturing is writing up protocols that can be executed by manufacturing employees – who typically have perhaps a certificate from a community college, and are most certainly not PhD scientists who are expert in the field.

Another aspect that is not GMP, but is just as vital, is to devise protocols that are actually optimized not only to give the best yields and results, but to do so robustly – meaning that they are not sensitive to poorly controlled factors, like small errors in measurement. This sort of optimization in manufacturing is how the Japanese figured out how to build high-quality cars in the 1960s, and totally kick the asses of American car manufacturers. I’ll bet that not one phage researcher in a hundred could tell you what a Taguchi Array or Response Surface Design is, let alone implement one to improve the quality of the products that they are testing on animals, and increasingly, people.

I was Director of R&D at MicroPhage, which developed the first (and still only) FDA-cleared phage technology product – an IVD which returned same-day results for S. aureus bloodstream infections and determined whether they were methicillin-resistant or -susceptible. MicroPhage was a small company, so being the R&D director meant also being responsible for product development and clinical trials.

To illustrate the difference between R&D and GMP production of phage, I thought it would be useful to compare a typical R&D protocol with part of our GMP phage production protocol.

Both protocols cover PEG/NaCl precipitation of phage. Because this procedure does not yield a very pure product (and CsCl gradient centrifugation is not scalable), we added a HPLC size-exclusion chromatography step, but I’ll spare you that protocol.

Here’s a typical R&D protocol, written by and for research scientists:

Nine steps. Easy peasy.

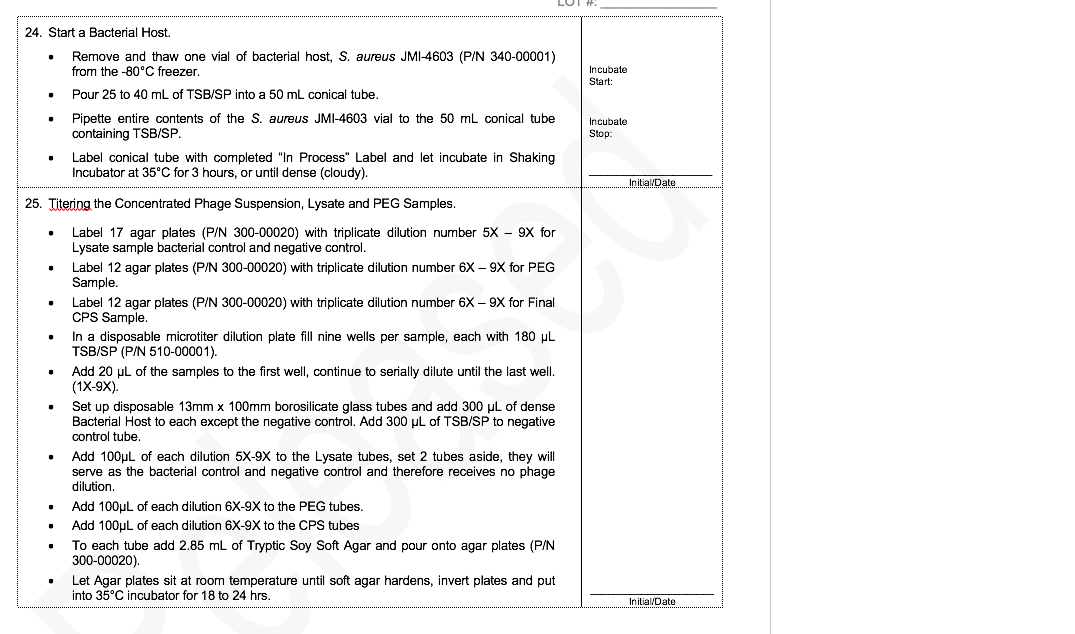

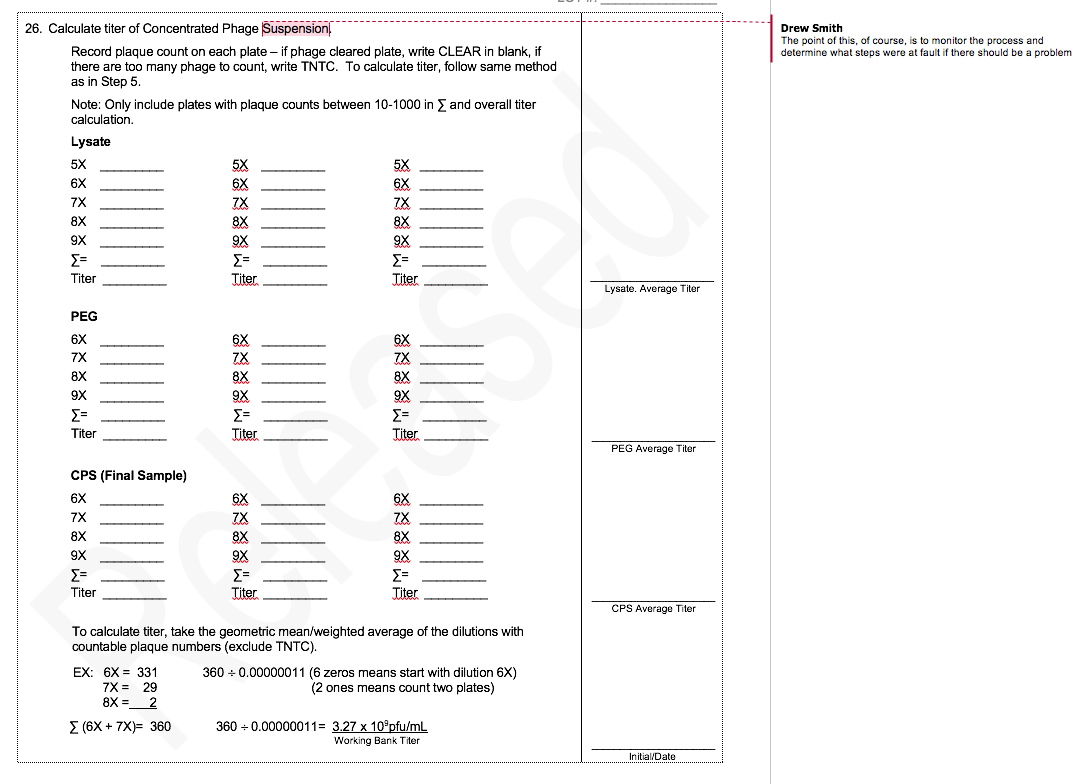

The MicroPhage protocol has 32 steps. I’ve annotated the places where we ran experiments that defined the optimum for that step. We had five phages in our cocktail, and each of them had a slightly different optimum.

If you are still with me – congratulations. There is nothing whatsoever intellectually interesting about developing these processes. They are just hard work. But absolutely essential to making a product that can reduce suffering and save lives. We need more of this kind of work in the phage field – a lot more. And until we get it, we are just going to keep getting excited about the occasional positive result and then turn sour when it can’t be repeated. That’s not okay.

1 thought on “Phage R&D vs GMP – an example”