I’ve been thinking about this for a while from the standpoint of biology. The basic business of the pharma industry is to find small molecules that bind to large molecules and alter their activities. There are lots of these large molecules (mostly enzymes and cell surface receptors), but “lots” does not equal “infinity”. And the number that control the course of a disease is smaller, perhaps much smaller. The supply of good drug targets has to run out someday.

The one drug-one target approach has been enormously successful. The WHO list of essential medicines is dominated by medicines that fit the one drug-one target paradigm: antimicrobials, painkillers, blood pressure meds, anti-inflammatories, anti-thrombotics, anti-depressants, anti-psychotics, cancer chemotherapeutics, contraceptives. Some are borderline fits: peptide hormones like oxytocin and insulin, or salts such as lithium. But peptides (and monoclonal antibodies), while not small molecules, still target discrete large molecules that are thought to be the root cause of disease.

This concept of disease – that it emanates from specific molecules behaving badly – may seem obvious to modern Westerners, but it is a novel development in the history of medicine. We’ve addressed so many diseases this way, though, that we’ve come to assume that we can treat all diseases this way.

But maybe not. Maybe there are only a finite number of key molecules that drive disease states by themselves. If so, these key molecules – drug targets – are a non-renewable resource. We should think of the rise of big pharma as a kind of gold rush for these drug targets.

Like any gold rush, the big fat nuggets were found first. Then it became necessary to pan in cold streams, or dig with pickaxes to gather up the gold gravel and sand. And then enormous expensive machines were needed to wheedle out the few specks of gold dust from mountains of dross. The rate of return – dollars of profit per dollar of investment – dropped steadily until it hovered near zero. What had once been a surefire investment became raw speculation as busts outnumbered bonanzas.

I knew that there are signs that this is happening in pharma – R&D spending is going up while the number of new drug approvals is flat or decreasing:

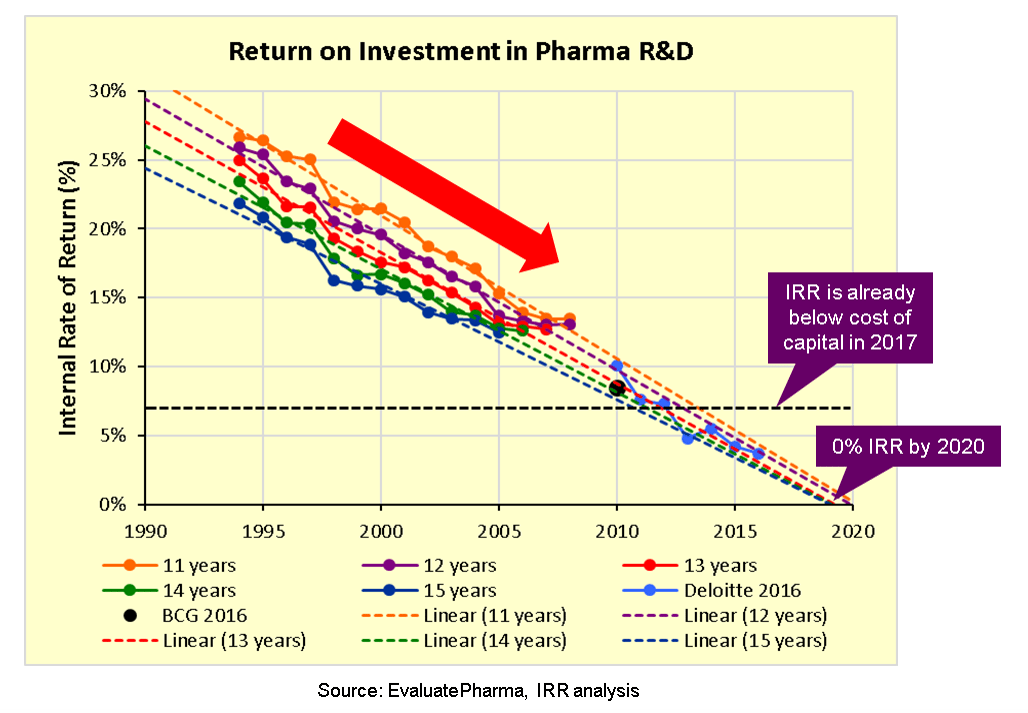

But a recent post by Kelvin Stott (h/t Christopher VanLang) works through the economic implications of this decline in a comprehensive and compelling way. You should follow the link and read Kelvin’s argument, but it boils down to this: Pharma returns on research spending are going down in all plausible scenarios:

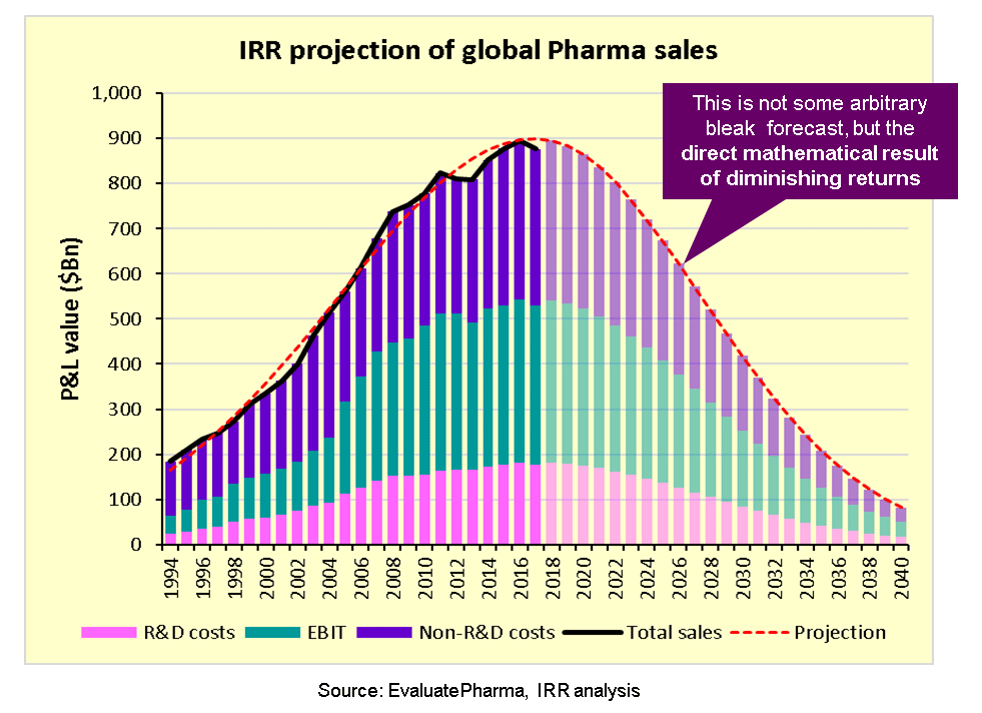

And using what I presume to be standard economic modeling, the consequence is that we have indeed hit Peak Pharma:

It’s all downhill for them from here.

There is no need to shed a tear of course. As Kelvin points out, pharma companies are full of smart people and have massive resources at their disposal. They will keep finding ways to make money, most of them anyway. They just won’t make money the same way that they have in the past. We may be seeing this already with the advent of cell-based therapies.

I’m not so interested in the fate of pharma companies as I am in how this trend may change our concepts of disease and medicine. Kelvin has confirmed something I thought to be only a possibility, and that makes the consequences worth thinking through a little harder. That will be the subject of a future post. Or several.

1 thought on “We may have reached Peak Pharma”